“I feel much the same - very bad; as a result of the previous events, I have completely “disappeared” from all concerts and Radio programs. If I was to say it in one word, for now, I am dead as a composer !, and when my resurrection will take place, I don’t know.”- Liatoshynsky

The above quote is from a letter that was written after Liatoshynsky received another ‘dose’ of severe criticism of his Symphony No.2. His Second Symphony was dismissed and performances forbidden; Lyatoshynsky was labelled as a ‘formalist’ and his music as ‘contrary to the people’. He now took on the aphorism:

“listeners love music, but do not understand it; composers understand it but don’t love it; critics neither love nor understand it.”

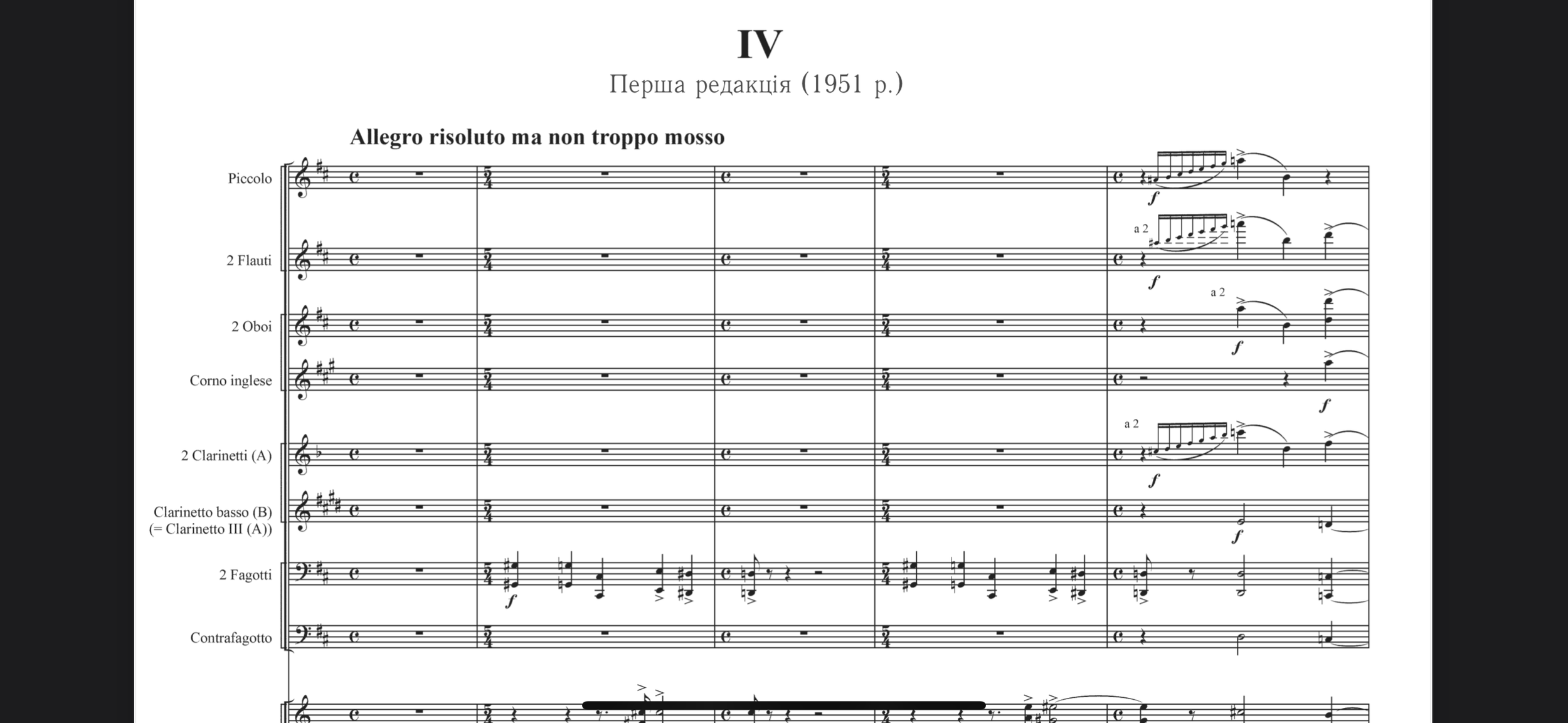

In 1951, the composer re-discovered his energy despite previous setbacks and carried on writing his Third Symphony which developed themes of heroic struggles placed against pessimistic dejection, which were interpreted by his contemporaries as epic philosophical themes of war and peace. Liatoshynsky presented himself as a demonstrative traditionalist, master of symphonic writing and the tradition of thematic development. At the same time, he considered structural and expressive forms of decay, deformation, mannerism, nihilism, sickness and convalescence. The Symphony establishes the connections with Liatoshynsky's keen interest in stylistic hybridity expressed through the use of the classical form, motivic development, atonality and primitivism of folk song. However, due to the censorship of the USSR and the label they placed on Liatoshynsky after the failed premiere of his second symphony, the composer was forced to adjust his third symphony and take away the title of the fourth movement due to the lack of USSR propaganda and representation.

There is now general awareness of the tragic effects of the gradual suppression of cultural life in the Soviet Union, with complete state control of all musical activities. By the late 1920s the Soviet government strenuously opposed the development of a national Ukrainian musical style, repressing all the arts and using them as a means of political propaganda, with a consequent disastrous decline in artistic standards. Eventually the Central Committee condemned the formalism of Western European music, while firmly controlling popular taste and the creativity of composers. Systematic purges and censorship enforced the principles of Socialist Realism.

TO THIS DAY, IT IS STILL HAPPENING. THE ATTACK ON MUSEUMS, CONCERT HALLS, AND ART GALLERIES IS MEANT TO WIPE OUT THE HISTORY OF UKRAINE

The Father of Ukrainian Contemporary Music:

Get to Know the Composer

Born January 3, 1895 in Zhytomyr, Ukraine. Died April 15th, 1968 in Kyiv, Ukraine

It is difficult to find a Ukrainian musician who is not familiar with Liatoshynsky’s Third Symphony, Op. 50, written in 1951 and revised in 1954, a work that provides yet another example of Party criticism. Generally considered to be one of Liatoshynsky finest compositions, and his most successful integration of nationalist and expressionist approaches, this work was first performed in 1951 at the Congress of Ukrainian Composers in Kiev. The premiere caused a great sensation; but Soviet censors were not satisfied and insisted that the composer would have to rewrite the last movement.

This finale, which had initially borne the epigraph ‘Peace will defeat war’, had to be substantially altered—and the epigraph removed—if Liatoshynsky hoped to see it performed again. After several years of agonizing indecision, he eventually offered a revised version in 1954; but it was only after yet more adjustment that the Party agreed to permit a performance. In its new form, the Symphony was given in Leningrad (St Petersburg) in 1955 by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra under the direction of Evgeny Mravinsky; and it was subsequently repeated in Moscow, Kiev and a number of other cities throughout the Soviet Union. Although the piece became an accepted and celebrated composition, the process of official rejection and forced revision proved hugely damaging to Liatoshynsky. The Party continued to level accusations of formalism, decadence, aggression, sadism and cacophony at his music, and it was not until the later 1950s that he felt able to operate once more with a sense of creative freedom. Despite this painful creative history, the Third Symphony is a supreme example of Ukrainian symphonic music, and stands among the most important symphonies of the twentieth century.

History

Liatoshynsky wrote a variety of works, including five symphonies, symphonic poems, and several shorter orchestral and vocal works, two operas, chamber music, and a number of works for solo piano. His earliest compositions were greatly influenced by the expressionism of Scriabin and Rachmaninov (Symphony No.1). His musical style later developed in a direction favored by Shostakovich, which caused significant problems with Soviet critics of the time, and as a result Liatoshynsky was accused (together with Prokofiev and Shostakovich) of formalism and creation of degenerative art. Many of his compositions were rarely or never performed during his lifetime. In 1993, a recording of his symphonies by the American conductor Theodore Kuchar and the Ukrainian State Symphony Orchestra (on the Naxos/Marco Polo label) brought his music to worldwide audiences.

During his time composing his second symphony from 1935-1938, while teaching at the Moscow Conservatory, he began experiencing struggles and difficulties through his compositions. His never performed second symphony which was supposed to be premiered in February of 1937, was gathering negative thoughts and comments from not just the local press, but from the Russian musicians claiming it to be unnecessarily complex and had absence of positive images of soviet life. There were even claims that it was 100% formalism. His second symphony only represented the dark reality of soviet life through his use of his favorite modernist style of composing painting these ideas through the use of atonality and dissonance. He now faced the hard reality of losing his identity and freedom to express Ukrainian culture.

In 1948, Liatoshynsky came to the National Conference of the Composers of Moscow (19th of April) even though he was excluded from the composers’ union of the USSR. With the reality of his situation, he expresses through his letters that he attended not as a composer, but as a participant. Before his now famous 3rd symphony could be performed, the USSR enforced that Liatoshynsky will discard his “old” way of composing and that his former works also be banned from performances. So long as he adhered to these commands, his future works would be premiered and performed.

Borys Liatoshynsky, 1960